Machine learning attempts de novo protein design

Model-driven protein engineering is the future of synbio. The ability to engineer proteins to do any chemical conversion imaginable (enzymes) or to perform complex biological tasks like edit or regulate genes would revolutionize the way we engineer biology. Existing tools however remain largely limited in what they can make, with most research still focused on getting designed proteins to fold correctly1, so protein engineering remains one of synthetic biology’s grand challenges.

Even the ability to redesign existing enzymes to function optimally under non-native condition remains a hard problem…

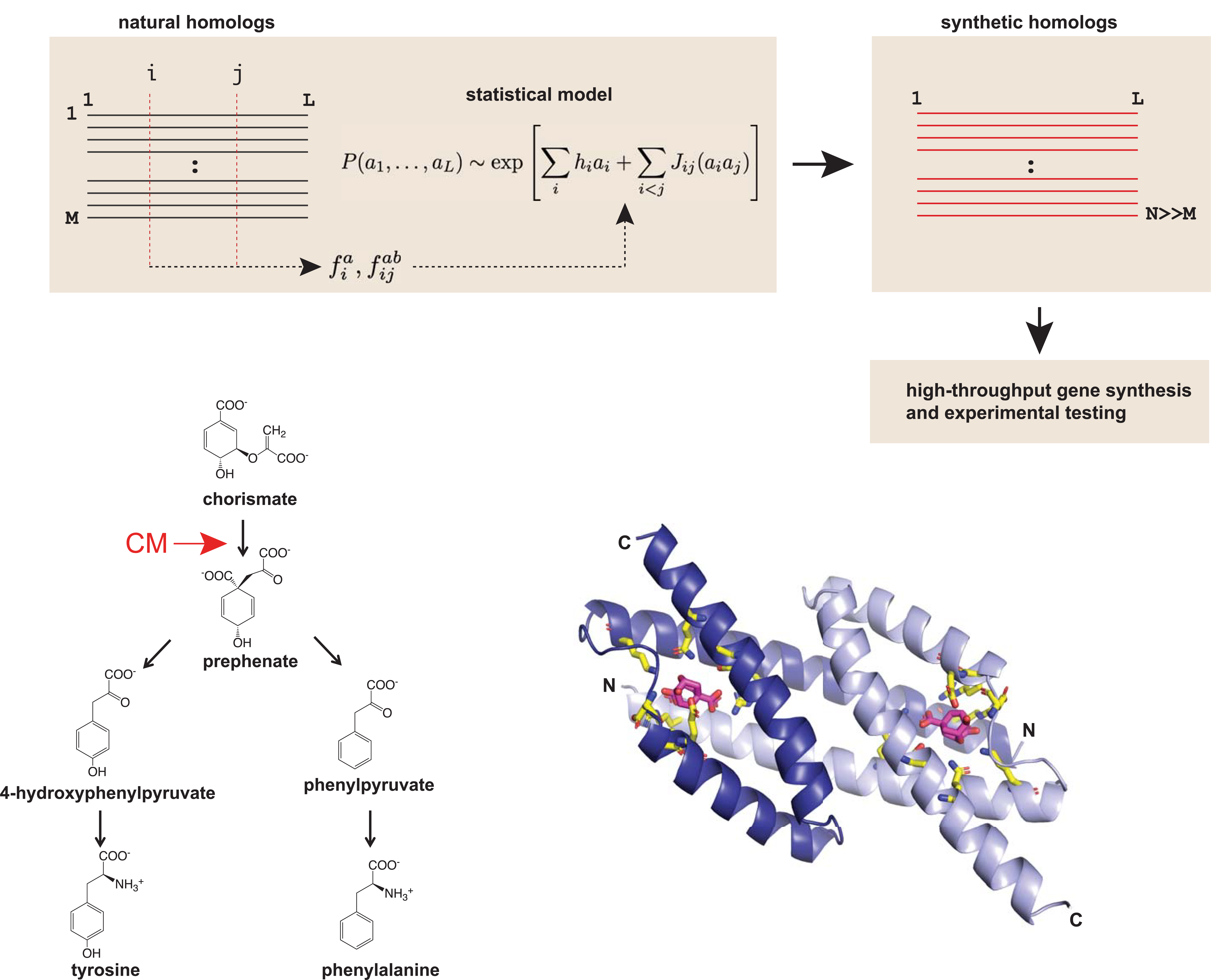

Back in July, a team of researchers demonstrated a novel approach for enzyme design that learns from existing enzyme sequences to design new ones. Published in Science, the approach uses machine learning to teach a statistical model the interaction couplings of an enzyme from thousands of natural homologs, and by sampling this statistical model, can design new functional enzyme variants with artificial amino acid sequences2. For the study, Russ et al. applied their model to design and characterize functional de novo chorismate mutase (CM) enzymes in E. coli with up to 82% sequence divergence from the natural E. coli CM.

The article interested me for a few reasons:

-

With machine learning, the authors train a statistical energy model that describes the pairwise interaction couplings of amino acid residues in a protein.

-

The model is trained using sequence information alone (no data). That is, they learn from evolution - thousands of variants of the same protein across many organisms (i.e. homologs).

-

The authors use a high-throughput experimental method that couples next-generation sequencing (NGS) and a selection-based assay in E. coli to screen for functional chorismate mutase variants.

At first I wrote a piece commending the work, but then I realized I didn’t agree with what I initially wrote. The research article has some glaring issues that make it problematic from a synthetic biologist’s perspective. So in this blog post, I decided to describe these problems with the hope of providing insight into how a synthetic biologist thinks about protein engineering.

Summary

Briefly, the model combines Direct Coupling Analysis with a machine learning technique called Boltzmann machine learning (bmDCA) to predict contacts between amino acids of a protein. The concept of DCA is to extract the observed frequencies and pairwise occurrences of the amino acids in a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) to infer a model that predicts the statistical energy of a new sequence variant3. Traditional DCA is extremely computationally intensive, but with the aid of Boltzmann machine learning, the authors were able to readily train the bmDCA model on 1,259 natural CM sequences from bacterial, archaeal, fungal and plant origins (top).

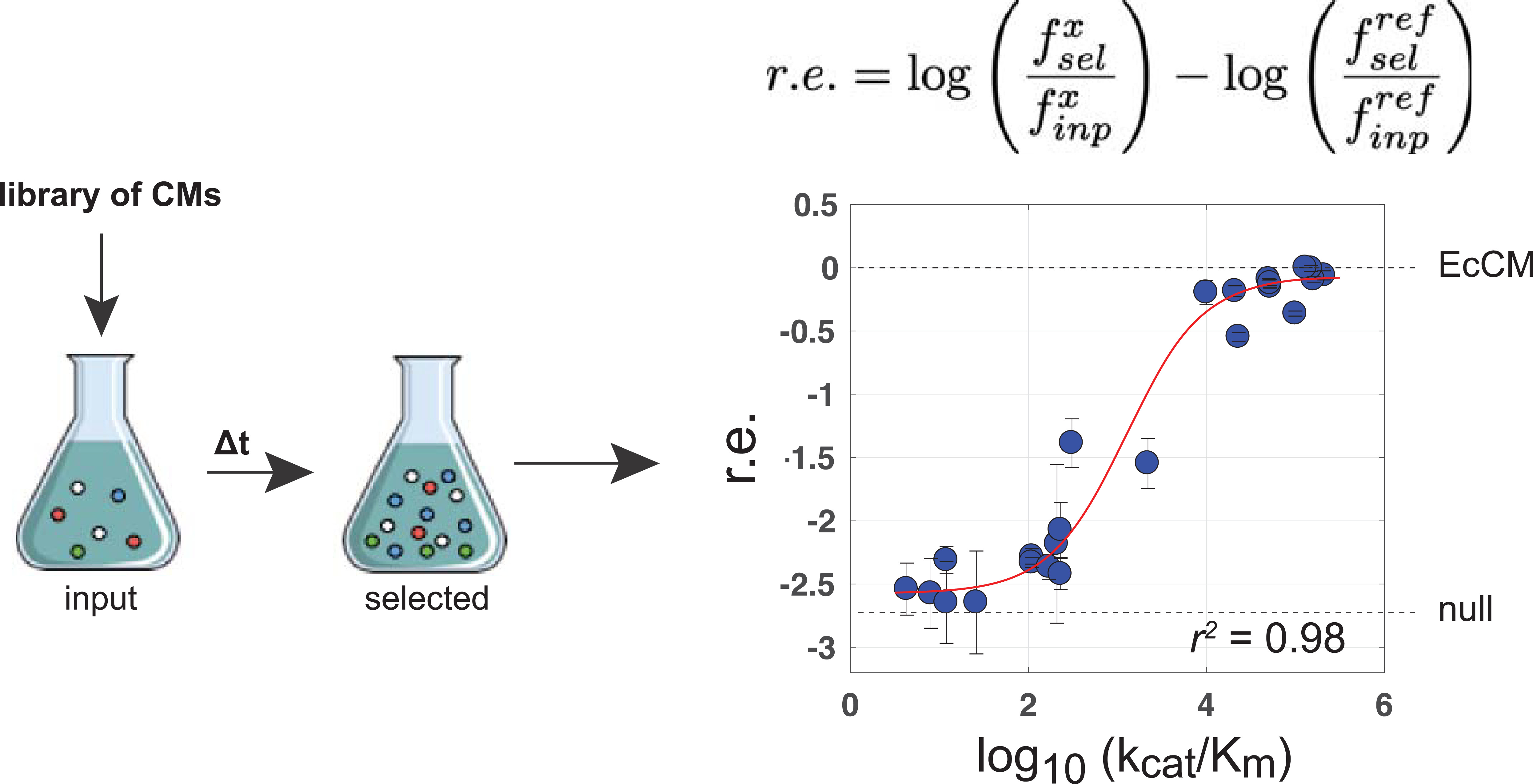

Next, the authors used a selection-based assay, termed select-seq, to screen a library of 1,618 model-designed CM variants. Chorismate mutase occurs at the branch of the shikimate pathway, an essential step for the biosynthesis of two amino acids, phenylalanine and tyrosine (bottom).

In order to test the CM variants, the authors transformed the library into a CM-deficient E. coli strain and grew the library in medium lacking phenylalanine and tyrosine. Deep sequencing before and after the assay was used to compute a relative enrichment score of each variant. Of the 1,618 artificial sequences, an impressive 481 variants (about 30%) rescued growth. Perhaps even more impressively, these protein sequences had only anywhere from 42 to 92% sequence identity to any of the natural CMs. The authors validated five of the enriched artificial CMs with a biochemical assay to show that they had natural-like catalytic activity, confirming that the enzymes designed were bona fide synthetic chorsimate mutases.

Many of the artificial variants however did not rescue growth in E. coli. The authors then sought to capture the missing information to explain why some CMs worked while others did not. They trained a logistic regression model as a binary classifier of function on the E. coli select-seq data. With this model as an additional filter on the bmDCA model, the authors were able to accurately predict the subset of artificial CM variants in the library that did rescue function. Significant positions identified by the logistic regression model revealed an arrangement of residues peripheral to the active site, suggesting a potential allosteric or indirect interaction with control over catalytic activity.

Some Issues

Put simply, the approach presented in Russ et al. is limited in what it can do:

1. The model can only redesign existing enzymes

The bmDCA model can learn a specific enzyme, such as chorismate mutase, but it can’t extrapolate and design other enzymes. It also cannot make significant changes to the enzyme, it can only design within a sort of sequence-design-space defined by the natural homologs. It cannot add domains, it cannot deliberately modify the shape or fold of the enzyme (although may do so incidentally by sampling the model and changing residues), and it cannot intentially modify properties of the enzyme such as folding stability or solubility.

It can make new enzymes, by sequence (de novo), that do the same function as the natural variants. The application of this, from a synthetic biologist’s perspective, is to design enzymes to function optimally out of their native-context. We call this heterologous protein expression. That is, you need an enzyme with a particular function in your organism of interest, and that organism doesn’t natively express that gene.

2. The design success rate is low, not much better than screening natural homologs

The problem however is that currently Russ et al. don’t have such a great design success rate. When the authors characterized the natural CM variants, about 38% worked in E. coli. In comparison, the artificial (designed) variants were that characterized and 48% worked! That’s not much better. It’s literally a coin-flip if the designed enzyme variant works or not. A synthetic biologist might as well just screen natural variants for functional ones in their target host organism.

3. The authors didn’t perform a final round of design with the final bmDCA-logistic-regression hybrid model

The authors somewhat acknowledge the shortcomings of the bmDCA model, and they perform “logistic regression” in an attempt to compensate for the missing information. They show that the bmDCA-LR model can correctly predict their existing data, but they don’t perform another round of design and characterization. I frequently see this in biological engineering research. Authors will do some modeling/design, show a result, show that their final model fits the result, but they often fail to really prove that the model can do true design with increased success.

4. Chorismate mutase is a relatively simple enzyme

I would leave The Issues at 1-3, as it makes a succinct story, but then I would fail to mention a key issue that protein engineers would probably raise first. The core catalytic domain of chorismate mutase that was studied in this work is one of the most simple protein folds to modify and design, an αβ-barrel4. Why is that an issue? If bmDCA hardly works for this enzyme, how can synthetic biologists expect it to work for anything more complex?

Parting Thoughts

Perhaps in the future the authors can build on this work to make a more sophisticated model that designs with higher accuracy. The bmDCA model can help scientists study enzymes to identify key interactions - without any data at all. That sort of analysis may be valuable to a scientist studying the protein of interest, even if it’s not that immediately valuable to synthetic biology.

More on protein engineering in the future.

References

-

Dill, K. A. & MacCallum, J. L. The protein-folding problem, 50 years on. Science 338, 1042-1046 (2012).

-

Russ, W. P. et al. An evolution-based model for designing chorismate mutase enzymes. Science 369, 440-445 (2020).

-

Morcos, F. et al. Direct-coupling analysis of residue coevolution captures native contacts across many protein families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, E1293-E1301 (2011).

-

MacBeath, G., Kast, P. & Hilvert, D. Redesigning enzyme topology by directed evolution. Science 279, 1958-1961 (1998).